| Main

Page |

Articles |

Translations |

"Because

I

was bored"

So,

in

the end, was it a captivating story? Yes, it absolutely

was. It occupied my thoughts wholly while reading it, and

then it kept me occupied for at least for a good few weeks

afterwards.

Though

I

actually do want to say it that ultimately, I was

disappointed in how little it dwelt on the philosophy of

the note itself. As much as the popular image of the manga

rests on the few chats and L and Light have over the

course of their dealings with each other as both friends

and enemies, the contents of said meetings are mostly

pragmatic in nature both from the perspective of the

characters and the story’s progress itself. Light and L

never really discuss what makes the two of them tick,

there’s never really an argument.

Most

likely

because the lines in the sand are clear. Everybody knows

which side they are on, and nobody will waver in their

faith, not even in the final moments of the great

showdown. They don’t discuss morality and ethics because

there’s nothing to discuss. The decision is made to use

violence to resolve their philosophical differences, the

actual discussion is therefore the plot of the manga and

the actions the protagonists take over the course of it.

But

I

think it’s worth mentioning that throughout the twelve

volumes of the manga, Light’s position is illustrated not

only by his actions, but also in the context of the

actions of others. He is the mastermind of the plot, but

at least two other people get some agency with the note,

illustrating how Light’s approach to killing/culling is a

sort of “golden mean” even if his position is ab ovo radical

when conferred our contemporary notion of a society based

on laws.

When

Light

loses the Note for the first time, we get a taste of a

“different Kira”. Higuchi is a motivated individual, but

his concerns are a lot more down to Earth. He fulfils the

obligations of brutalizing criminals and filling in for

Kira, but all he does on his own accord is manipulate the

business world to climb the corporate ladder and corner

the market with his associates.

Higuchi’s

style

of using the Note highlights the unusual moral fibre of

Light’s personality. He could have done the same thing

very easily, but ultimately, he decided to go beyond

seeking wealth and temporal power.

Mikami

Teru’s

use of the Note is also a commentary on Light’s own

methods. Mikami is probably as close to Light as one could

get on the surface. A perfectly focused, methodical mind.

His biggest fault is his endless lust for purity and his

inability to deviate from his standards.

Mikami’s

boundless

wish to deliver justice results in his cruelty knowing no

bounds either, shocking even Light. Mikami shows no

tolerance for any deviation from the norms, and he shows

no remorse in punishing those breaking the rules. Light

doesn’t punish people for minor traffic violations, simple

accidents or for the crime of Acedia/ἀκηδία,

that is, unwillingness of someone to do their social and

work obligations. He’s fully ready to immediately strike

down elements he considers “asocial”, something which

Light himself is shocked to see in its totality. (But

confesses that he himself would have done the same

eventually, but in this regard, we can see Light’s ability

to bide his time, and that he tries to achieve his goals

of building a perfect society in an almost Buddhist

manner, where people are gradually purified and awakened

to the idea of building the perfect society around Kira’s

(cult of) personality and through his guidance.

One

could

say that the uncompromising, cruel Mikami is the

embodiment of a Chinese legalist, which is true if we go

Sima Qian’s 司馬遷 depictions of

Qin Shihuangdi 秦始皇帝 as an uncompromising tyrant-king whose cruel

mode of conduct both in personal affairs and in governance

lead to his empire’s downfall. Of course the same Sima

Qian details how Qin Shihuangdi enjoyed a good laugh,

allowing his court-dwarf, You Zhan 優旃 to make clever

quips about his policies. (Like when the emperor wanted to

extend the hunting grounds, You Zhan remarked that if the

enemy comes from that direction, then they can just ask

the deer to take up arms and fight them. While a funny

remark, the emperor heeded his warning and decided to not

extend the hunting grounds due to the mentioned strategic

concerns. But I digress.)

Ultimately this

little digression only serves to illustrate that “What is

a legalist?” is a tricky question to answer, mostly

because of how the “legalists” themselves did not

compromise a single unified school in the Confucian/Motian

sense. This, coupled with hundreds of years of Confucian

supremacy and slander at least on the ideological (not

practical) side of things means that there’s not one

definition of “legalism” we could reasonably settle on tho

answer this question.

Though that is

not to say we can’t entertain the thought for at least a

bit by contrasting the manga and primary sources of

Chinese legalism in the following section once I wrap up

interpreting the manga itself.

So, we can say

that Death Note doesn’t really comment on morality or

ethics, but it does comment on itself by handing the Note

to different characters with a diverse number of

backgrounds an motives to showcase us how Light isn’t

necessarily the embodiment of pure evil.

Ultimately, Death

Note is not as much a thriller as it is a tragedy of

Yagami Light’s failure to moderate himself when handed

absolute power to do as he wishes. Time and time again the

manga showcases an alternate version of him, who is an

upstanding member of society in the service of the public.

It’s reasonable to interpret that without the Note, Light

would have become a sensible police officer who would have

gone far in the force in his quest to stamp out crime,

would have been a good father and so on. But when given

the chance to let his ideals bloom and to escape the

desolation of boredom and the pain associated with it, he

immediately jumps at the possibility without looking back.

Death Note is

just as much the tragedy of absolute power corrupting

absolutely as it is a tragedy of genius going unstimulated

and unused, it putting itself to the path to ruin just to

escape the ultimate evil, boredom, not much unlike Conan

Doyle’s Sherlock who does cocaine not to enhance his

senses but to take his mind off the predictability of

everyday life.

But

let us discuss something more stimulating too, considering

probably everyone has come to a similar conclusion after

having almost 20 years to ponder it.

Is

Yagami Light a Legalist?

Firstly,

we

must establish our viewpoint. He's a legalist to whom

exactly?

From the viewpoint of society's elite, Light is not a

legalist. He is way too

independent for that. Light takes the law as a basis,

sure, and pays

lip-service to upholding it, but ultimately, he makes up

his own punishment and

criteria for writing names in the Note. Essentially,

within the existing

framework of the justice system and legislation, Light

is a lousy subject for

the opposite reason people are: That it, he is

overzealous and does too much

compared to what is set out in the letter of the law.

This

might

sounds stupid to an outside reader: "Why punish

over-achievement the

same way you punish underachievement?" they might ask.

Well, it's all

about procedure and initiative. As Lord Shang says in

the Xiuquan 修權

chapter of his book:

國之所以治者

三:一曰法,

二曰信,

三曰權。法者,君臣之所共操也;信者, 君臣之所共立也;權者,君之所獨制也。

人主將欲禁姦,則審合刑名者,言異事也。為人臣者陳而言,君以其言授之事,專以其事責其功。功當其

事,事當其言,則賞;功不當其事,事不當其言,則罰。故群臣其言大而功小者則罰,非罰小功也,罰功不當名也。

If

the

lord of men wants to forbid treachery, he must clarify

the correspondence

between names and punishments, and teach them to

differentiate between names.

When a subject makes a statement and speaks, the ruler

gives them a task taking

their speech as measure, and then makes sure that the

results are in

correspondence with their tasks exactly. If the results

are as the task, and

the task are as his words, then he is rewarded, but if

the results are not like

the task, and the task is not like his words, then he is

punished. Thus the

multitude of ministers whose words are big but results

are small are punished.

Those of little results are not punished, for only the

results not

corresponding to the names are punished.

From

both

quotes, we can gather that in Legalism, evaluating the

action of others

and setting the measures for the evaluation itself

belong to those in power.

(In the case of ancient China, the Wang/King or the

Huangdi/Emperor.) Light

himself is but a lowly citizen aside from the Note, so

his infringing on the

monopoly of the state/government in setting laws and

judging those who break

them, he rightfully upsets the defenders of the status

quo.

So attacking

from this angle, it’s pretty simple to

conclude that Light is a terrible person who causes a

lot of luan 亂 or chaos within the

workings of society, upsetting the stable if imperfect

status quo. But this

conclusion would be onesided and thoroughly unamusing,

which is why I’m going

to amuse myself a bit more by taking an approach I have

to thank Xianyang City

Bureaucrat (@XianyangCB) for

introducing me to.

It’s not so

much that this is such a revolutionary

idea, rather, I was personally limited by my own lack of

political education,

experience, and ambition. Namely: Let’s analyse the

situation from the perspective

of not a government in charge, but rather from the

viewpoint of an upstart, an

usurper. Someone in ascendancy who seeks to re-establish

the existing,

crumbling order using raw power.

Light fits the

image of the up-and-coming tyrant

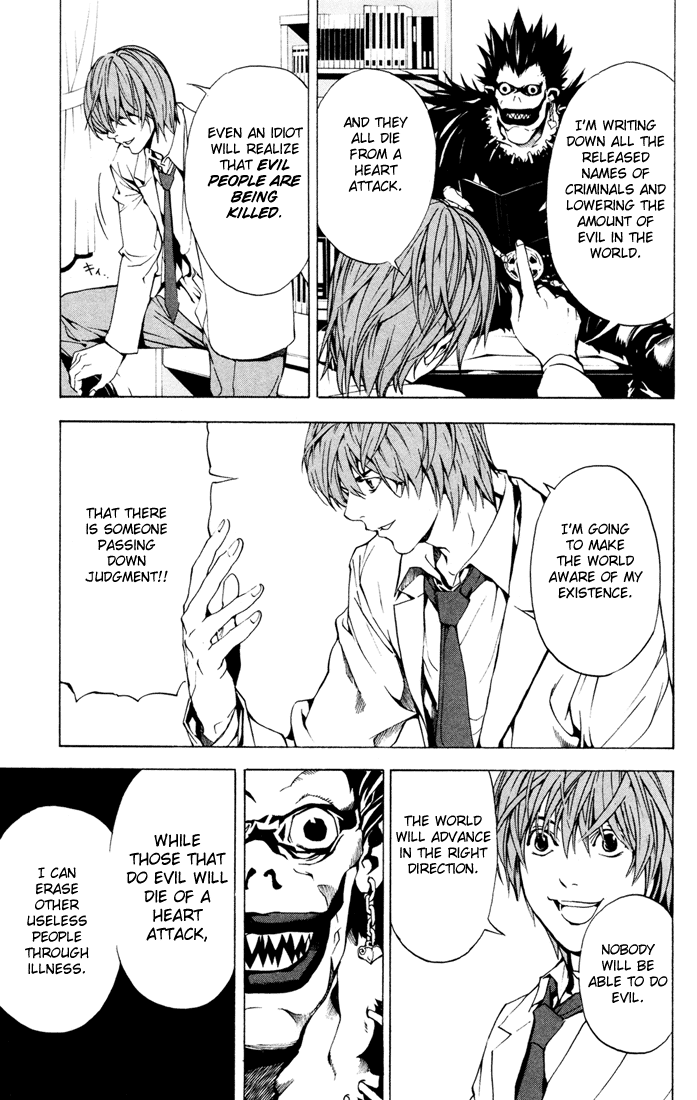

much better. A good illustration of his legalist

tendencies is his reasoning

(one of the more explicitly philosophical moments in the

manga) for using the

Death Note to kill criminals in the manga:

Let’s contrast

this with both Shang Yang and Han

Fei:

Shang Yang

writes in the Kaisai 開塞 chapter of his book:

故王者以賞禁,以刑勸;求過不求善,藉刑以去刑。

Therefore the

ruler uses rewards to limit and

punishments to motivate. He seeks out wrongdoings

instead of seeking out good

deeds. He relies on punishments to eliminate

punishments.

While Han Fei

writes in Wu du 五蠹:

是以賞莫如厚而信,使民利之;罰莫如重而必,使民畏之;法莫如一而固,使民知

之。故主施賞不遷,行誅無赦。譽輔其賞,毀隨其罰,則賢不肖俱盡其力矣。

Thus when

rewards are given they should be generous

and reliably handed out, so that the people may gain

benefit from them.

Punishments should be harsh and certain, so that the

people come to fear them.

Laws are great when they are unified and stable, that

way the people learn

them. Thus when the ruler hands out rewards, he does

not change them, and in

handing out punishment he does not show mercy, this

way both men who are

outstanding and the unworthy will do everything in

their power.

夫聖人之治國,不恃人之為吾善也,而用其不得為非也。

Thus when

governing a country, the sage does not

rely on people doing what is good for him, rather, he

makes use of them not

being able to do bad things.

Here we can see

a clear parallelism with Legalist thought

in Light’s reasoning for brutally striking down

criminals. Essentially you can

make sure that people don’t act out of line and

brutalize each other if you use

a higher power (all-certain brutal judgemental

authority).

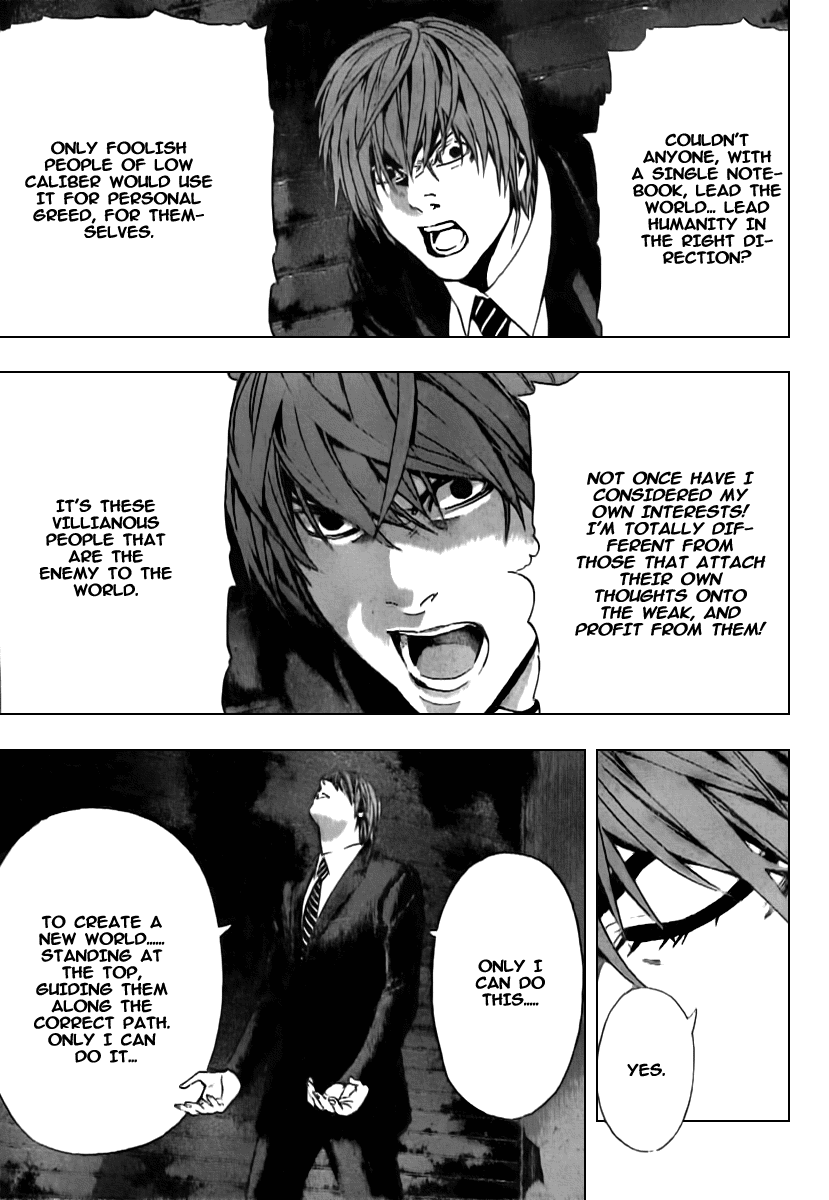

Light sees

himself as an impartial authority who judges

appropriately for the sake of society, not for the

sake of himself. Unlike

Higuchi, who abuses the Note to gain immense wealth in

a market economy, Light

never uses the Note for personal gain, in line with

Han Fei’s warning to rulers

who are too fond of acquiring treasures and other

items for personal use:

饕貪而無饜,近利而好得者,可亡也。

If the ruler

is greedy and insaitable, covets profit

and is fond of acquring things, then his fall is

certain. (Hanfeizi:

Wang zhi 亡徵 chapter)

But it is

absolutely worth mentioning that Light

isn’t as strict and severe as you’d imagine an

arch-legalist to be based on sources

such as the Records of the Grand Historian. He shows

compassion, and

understanding to those that merely had accidends or

the circumstances forced

them into commiting a questionable act. Which is

coincidentally, also closer to

actually existing legalism under the Qin dynasty. For

example, the legendary

story of revolts breaking out because an army was late

and the punishment for

rebellion and being late were both death were proven

false by archeological

sources which report that being late with an army unit

only carried financial

penalties, and the penalties were waived in case the

weather prevented the troops

from marching at sufficient speed or at all. So by

mere coincidence, Light does

not fit the stereotypical, propagandistic image of a

legalist being cruel and

without compassion, but he’s quite close to legalism

as it actually existed

most likely during the peak of he First Emperor’s

reign.

Another

important component of the manga is secrecy:

Someone else figuring out your thinking is equal to a

death sentence. Both L

and Light go to great lengths to either confuse the

other or to obscure their

own intentions when making moves, which is similar to

how Han Fei recommends a

ruler not to allow even his ministers to know his

thought patterns. (Though it

is worth mentioning that in Han Fei’s case, this

warning wasn’t against

potential coups or plots in the strictest sense,

rather, against one minister

becoming so good at doing things that makes the ruler

happy that it would result

in favoritism and monopolisation of the ruler’s

attention, thereby weakening the

impartiality of government. But the principle is the

same: Secrecy is power,

and the less someone knows what your potential moveset

is, the more they fear

you.):

故明主觀人,不使人觀己。

Thus the ruler

who sees things clearly observes

other people, but does not allow other people to

observe him. (Hanfeizi: Guan xing 觀行 chapter)

Yagami Light

might use legalist methods in his

approach and see himself as an enlightened, impartial

sovereign, but for example,

he does not hold fast to the belief that all men are

inherently evil and that “goodness”

in people is something that is only created through

artificial indoctrination

(a la Xunzi[1]).

In

his grand monolgue and final attempt at convincing his

opponents, Light

genuinely seems to believe that there are upright

people in society who are not

only capable of not doing bad things, but rather,

would be capable of exerting

justice upon others, with his father being a chief

example. (It’s also very interesting

to note that what actually becomes the final trigger

in that makes Matsuda

doubt and lose faith in Light’s argument is the lack

of filial piety (xiao 孝) on Light’s part towards

his father, that is, sacrificing family for society.)

Just the

same, Light doesn’t intend to just let

people avoid acting evil, ultimately, his goal is a

utopia, and for that he

intends to weed out those who are unwilling to

contribute to society. Ultimately

the argument can be made that Yagami Light is a

committed legalist when it

comes to his methods, but his vision goes beyond the

goals of legalism, because

he ultimately seeks to not just crush evil activities,

but he wants humanity to

reach ever greater heights and harmony with itself.

[1] Who

was not a Legalist, but whose

intellectual contributions to the bleakness of the

legalists’ views on human

nature is unavoidable to mention.