Crime fiction is one of the most popular genres

in literature, and has been almost since its conception in the

late 19th century. Figures like Sherlock Holmes and Arsene Lupin

captivated our imagination for well over a hundred years at this

point. Asia is no exception: The Chinese and the Japanese love

and have loved stories of detection for a very long time in one

form or another.

But what about modern times? How did European crime fiction

influence Asian popular culture? The answer is obviously:

Profoundly.

This article will deal with the relationship of Edogawa Ranpo's

江戸川 乱歩 The

Fiend With Twenty Faces (怪人二十面相, Kaijin

ni-jū Mensō) and Maurice Leblanc's third novel

starring Arsene Lupin, The Hollow Needle (L'Aiguille

creuse).

(The article contains spoilers for the

two books!)

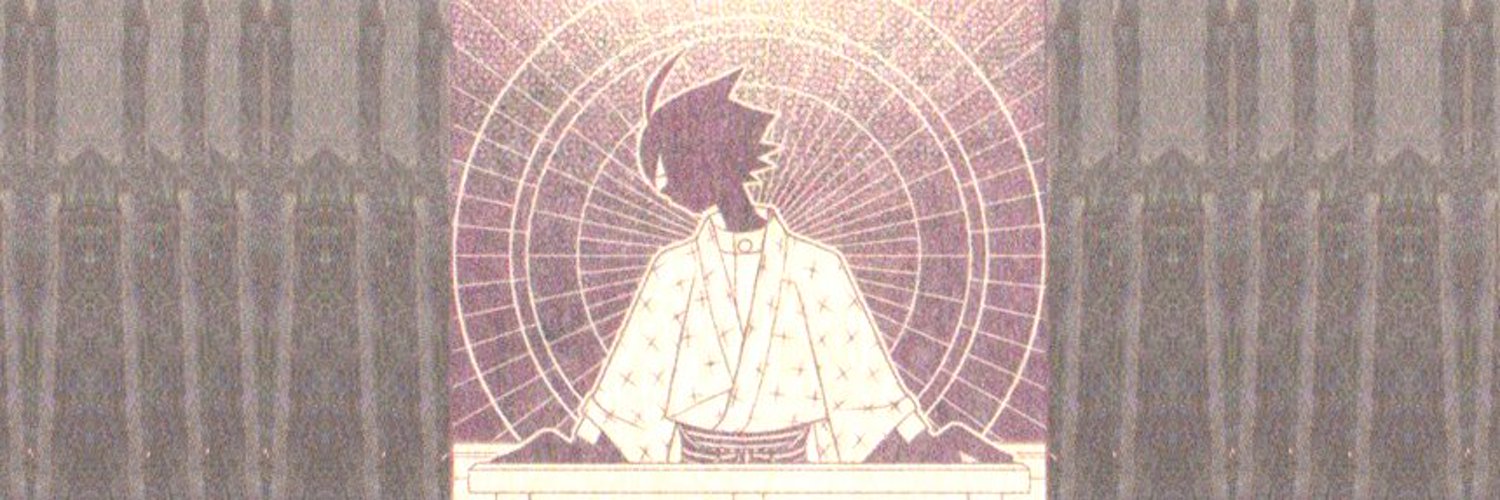

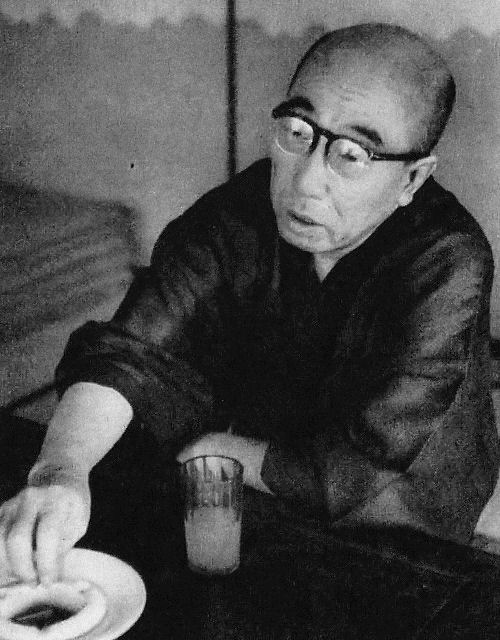

Edogawa Ranpo (Left) and Maurice Leblanc (Right)

Edogawa Ranpo (Left) and Maurice Leblanc (Right)

was published in 1909 and contains the

third adventure of Arsene Lupin. In a sense, Leblanc was trying

to tie up some of the loose threads before changing his mind in

the last minute.

Plain and simple: The Hollow Needle's plot is about Arsene Lupin

trying to retire and escape into civilian life from being a

master thief, with a woman he loves. To this end, he leads the

police by their noses on a chase across France until they find

his secret lair in Normandy, allowing the French state to occupy

his secret fortress under a rock called "The Needle" in Étretat.

Of course, in the final moments of the climax the woman is

killed by a stray bullet and Lupin's fate is left uncertain.

Will he still escape into civilian life with his lover dead and

lair exposed or will he return to a life of grandiose crime?

Considering there's at least a dozen novels following this one,

the answer is probably the second option, but I digress.

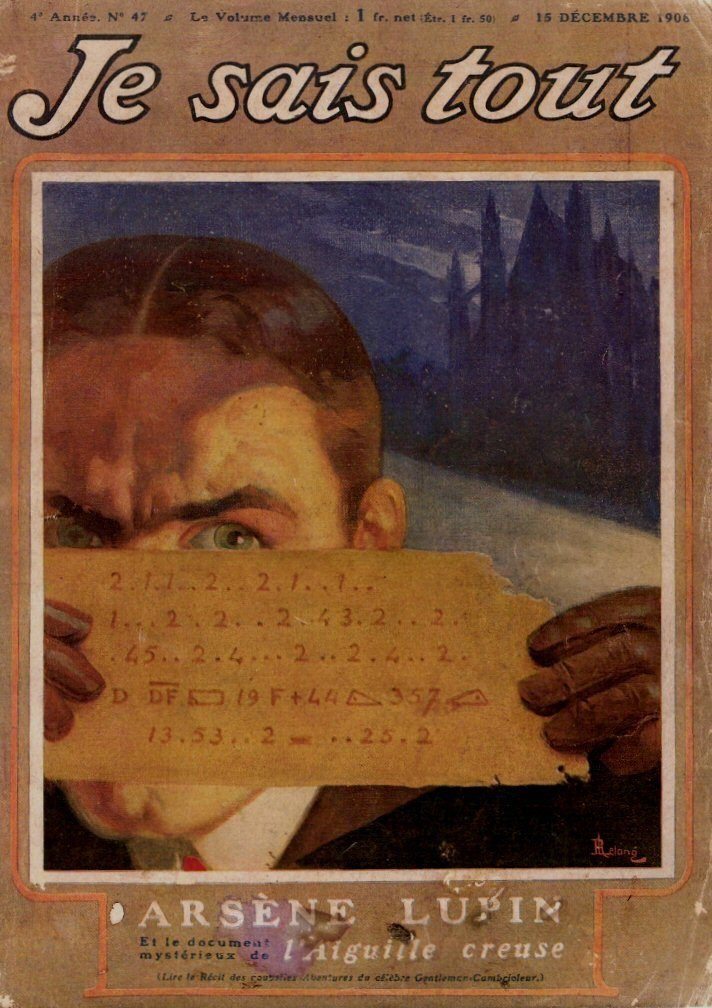

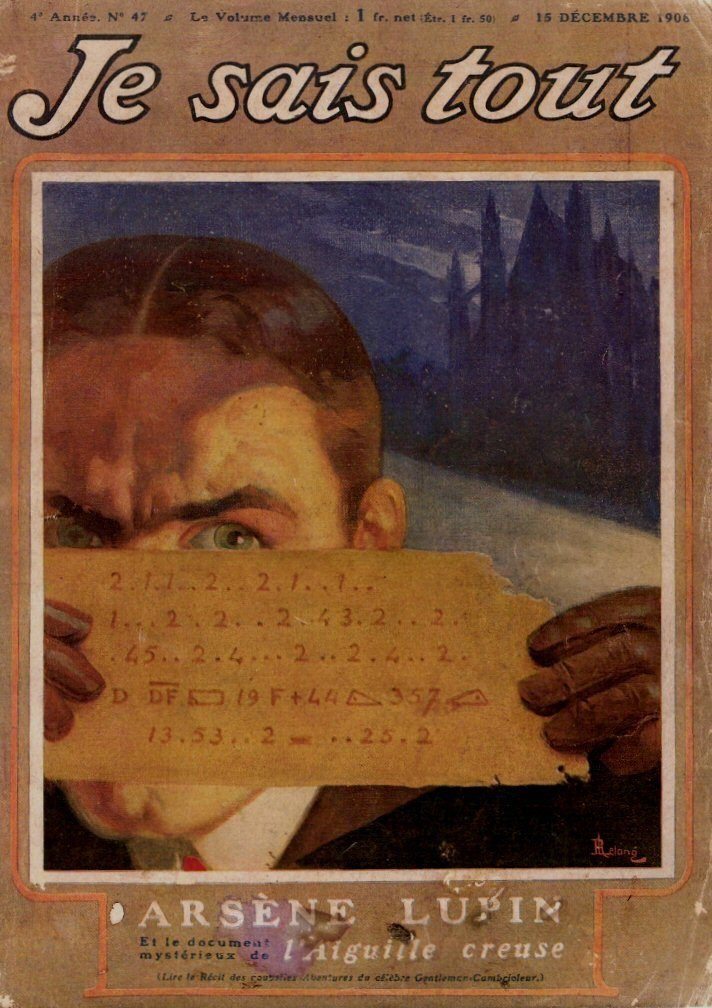

Cover of the 1909 July–December issue

of "Je sais tout"

featuring Leblanc's story

Far more interesting than Lupin's struggles with love is the

other main character of the novel:

Isidore Beautrelet.

Beautrelet turns up at one of the scenes of Lupin's crimes just

as the police is conducting their investigation. He immediately

sets out to work, deducting the details of the crime with

relative ease while wearing a fake beard. Why the fake beard?

Because he's only a young student at one of France's many

Lyceums.

The curious detail in this is the fact that Leblanc creates a

teenage detective all the way back in 1909. High schoolers

solving crimes... Sounds like something out of an anime or a

manga, and we could brush this off as simply a mere coincidence,

thinking the Japanese arrived at the same premise without the

influence of Leblanc's writings, but we would be thoroughly

wrong if we did that! In essence, stuff like Detective Conan or

Akechi Goro's figure in Persona 5 have a lot to thank Maurice

Leblanc for, and all of this can be traced back to one man:

Edogawa Ranpo! (Sometimes written as "Rampo" in accordance with

old-style Hepburn.)

Edogawa Ranpo was a prolific author of crime fiction in the 20th

century, being at the forefront of developing a quality

tradition of crime fiction writing in Japan as the country was

modernizing during the Taisho and Showa periods. Ranpo's fiction

oftentimes carry on the Taisho spirit of writing in a liberal

manner, depicting

femme fatales, strange situations like

hiding in chairs or people with grotesque appearances and

deformities. He himself identified his writings as belonging to

the tradition of "Eroguro nansensu" or "Erotic and grotesque

nonsense".

Logical reasoning played an important role in Ranpo's early

stories such as

Murder on D-Hill. This he inherited

from Arthur Conan Doyle, and his most famous character, Akechi

Kogoro was indeed a Japanese attempt at trying to "domesticate"

the figure of the master detective from Britain. From his first

appearance in 1925, Akechi's figure was a constant feature of

Ranpo's works and his character slowly developed from a poor,

bookish university student wearing a kimono to being a

much-travelled, world famous sleuth with considerable flair. In

essence we could say that Ranpo's character modernizes alongside

Japan, and can be understood as a cross-cultural attempt at

grappling with all the new ideas, inventions, fashion and

technology flooding into the country, resulting in not only much

change but also an increase in the nation's competence and

confidence both at home and at abroad.

His 1936 novel

The Fiend with Twenty Faces is part of

his output targeting juvenile readers of the era. To this end

his iconic master detective gets a small assistant by the name

of

Kobayashi Yoshio. Of course viewed in literary

isolation using our general knowledge of Japan's contemporary

popular culture, this seems like a typically Japanese thing. But

just as with many things dubbed "stereotypically Japanese", the

roots lie abroad, even if buried deep underground by time.

Just like Beautrelet, Kobayashi is very autonomous. He's not

afraid to act even without permission. Akechi's tutelage is more

of a protective umbrella for when the situation turns too

serious. Essentially he's a higher power intervening, making

sure that harm doesn't get in the way of adventure for the

self-inserts of the young readers. (This is of course, also in

accordance with the demand of the times during a period when

authoritarianism was on the rise, demanding good role models for

young boys.)

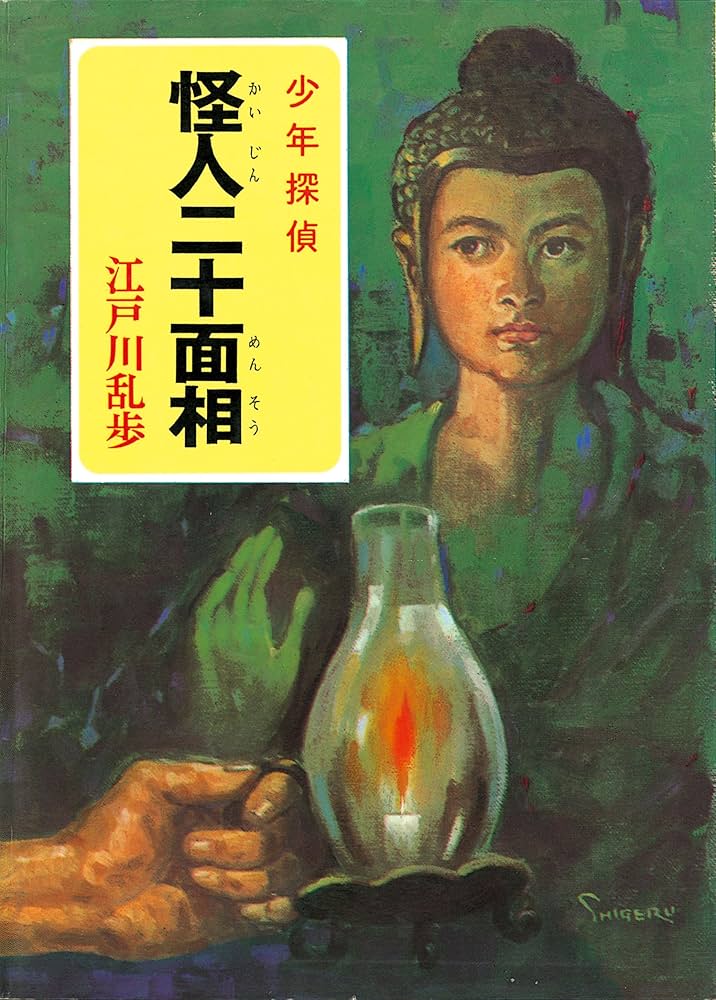

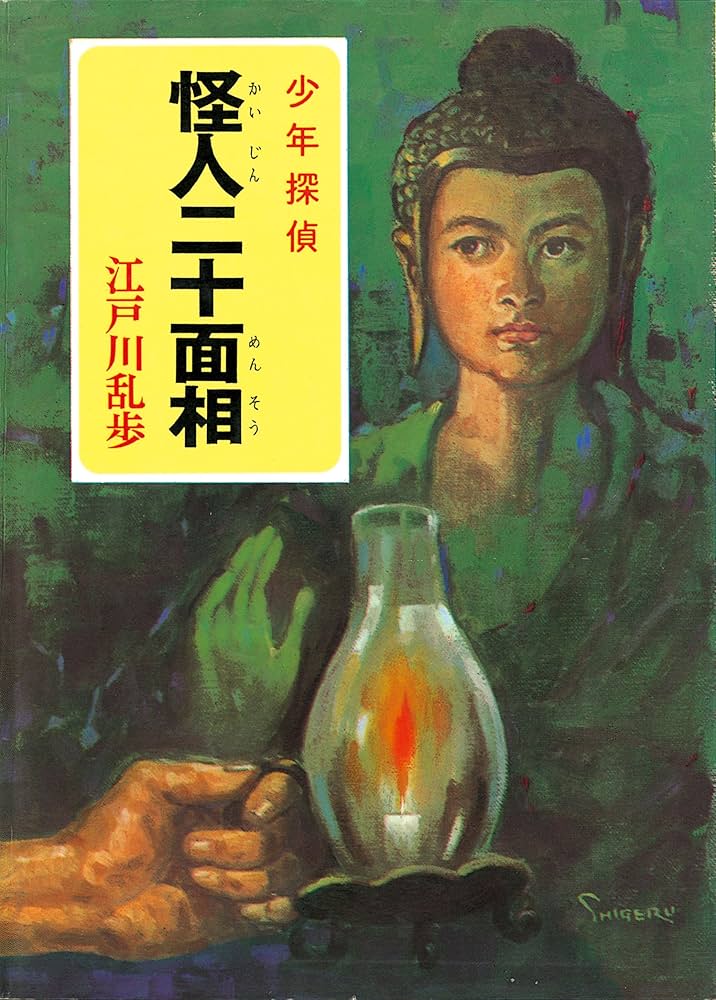

Japanese edition of Ranpo's

Fiend with Twenty Faces

Kobayashi's character has been influenced by

that of Beautrelet, and while just their similar age and

attachment to detective work might not be the kind of proof

that would satisfy most people, the environment into which

Ranpo places his new character serves with definite proof of

where he drew his inspiration from.

First off, we have to look at who he faces off against.

Kobayashi's opponent in the book is called

Twenty Faces,

a thief who is a master of disguise. The influence of

Leblanc's Lupin is much more clearer on Twenty Faces, from

his occupation and methods down to the point where he spends

so much time in disguises that nobody is ever sure what his

face actually looks like, just like Lupin. He also sends a

calling card before stealing the treasures that caught his

eye.

Following getting injured by an unexpectedly laid down trap

during the first heist of the book, Twenty Faces finds

himself stuck in the garden of the Hashiba family. With all

exits closed off by policemen, the situation is not quite

unlike the one Lupin experiences in the first part of

The

Hollow Needle where he is injured during a botched

heist.

Then there's also the larger structure of the novel, where

both Beautrelet and Ranpo's protagonists are after their

respective thief's hideout. Of course the plot is not quiet

as serious and convoluted in Ranpo's book as in Leblanc's,

but the overall aim is the same: Find their central hideout

and put an end to their series of heists once and for all!

Though it is worth mentioning that in Ranpo's novel, Twenty

Faces is not seeking to retire, so his "failure" is not part

of some secret plan, he's simply foiled by Akechi and

Kobayashi.

This shows us that Ranpo wasn't just importing and

Japanizing character archetypes, he was also adapting

setpieces from Western crime fiction.

The final clue is Kobayashi's remark in the early parts of

the novel, where he tells the anxious Mr. Hashiba his plan

and also tells him that:

"Last year, in France, Mr. Akechi

gave the phantom thief Arsene Lupin a nasty shock using

this very method."

This is essentially Ranpo quite

literally telling the reader about his inspirations, but

it also is a stepping stone for elevating his setting.

In quality, in cleverness, Ranpo treats his characters

as equals of their western counterparts. Japan has grown

a lot. Grown up.

Ranpo's story is essentially a respectful handshake

between East and West. This is exactly why this 1936

novel is so fascinating to read when placed in the

proper literary context. He carries on not only the

character types and spirit of detective fiction, but

also the tradition of using and referring to other

authors' characters by whom he was inspired by or he

looks up to. (Such as with Leblanc initially penning his

Lupin stories with his character facing off against

Sherlock Holmes, before being forced to change it due to

copyright reasons.)

The Fiend with Twenty Faces remains a rather pleasant,

albeit short read, even as it's getting close to turning

90 years old. In 2017 it received an English

translation, making this classic piece of juvenile

detective fiction available to people outside Japan.

Even if you don't necessarily care about the convoluted

intertextual web relating it back to its European

forerunners, it's still worth a read just to see how

this seemingly obscure book might have influenced your

favourite anime or manga without you even knowing it!

The article was based on the following editions:

Maurice Leblanc (2021): Az Odvas Tű Titka, GABO,

Budapest. (In Hungarian, Translated by Gábor Bittner)

Edogawa Rampo (2017): The Fiend With Twenty Faces,

Kurodahan press. (In English, Translated by Dan Luffey)